I find many joys in my local library. It’s something I could go on and on about, but I’ll save that joy for another post…

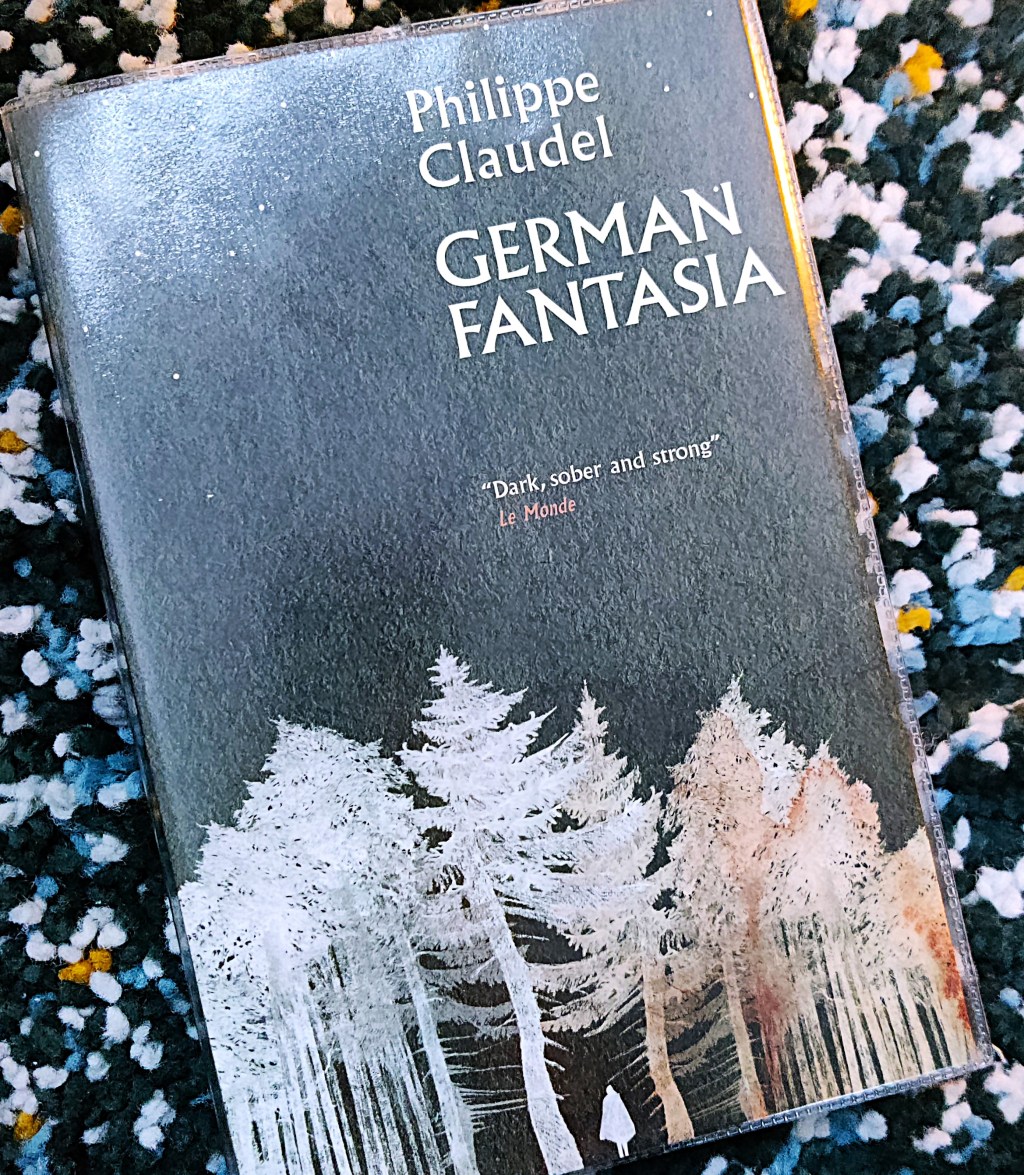

This month I borrowed a copy of German Fantasia by Philippe Claudel from my library. It’s a short story collection of 150 pages detailing the stories of individuals surrounding the second world war, and recurring mentions of an antagonistic character, Viktor.

The first story in the collection, Ein Mann (A Man), follows an unnamed guard on a continuous journey to avoid persecution from opposting forces or restitution from his abandoned one. In just twenty pages, Claudel has reduced me to tears. I was rooting for this character who, completely exhausted by his journey, was spurred to continue by remorse and guilt for his actions, and a promise to never do it again.

The second story of the collection, Sex und Linden (Sex and Limes), follows the final days of a ninety-year old, his vision and hearing degrading the perception of his surroundings, supplemented instead by his memory. The story merges past and present, with small details taking the man back to times long passed, at a concert hearing Hadyn shortly after the war. The vivid descriptions used by Claudel placed me in that shady area of the park, the smell of limes in the humid, summer air, lulled by classical music.

For me, Die Kleine (The Little Girl) was the most moving story in the collection. The Girl notes how she came to live with the Woman, providing details of before events – of a kind man who led her off a truck, and the last time she saw her parents alive. Die Kleine positions the reader to read between the lines, making clear the murky, harrowing details the Girl provides. Placed at the end of the collection, Die Kleine inspires readers to make connections to the previous stories, providing a sense of closure and forward momentum.

Though many like to take a work as it is ( Barthes “death of the author”, and such), German Fantasia contains a final note from Claudel To The Reader. In it, Claudel explains his choices in using real people as characters, specifically Wilfried F. Schoeller, his references to the Nazi’s Aktion T4, and the inclusion of a letter written by Hitler in 1939, an order which authorised the extermination of psychiatric patients.

Further in this section, Claudel notes that there is “a call to the reader to fill the gaps by becoming a writer themselves.” This is true in that, throughout the collection, the reader is invited to ‘create’ the antagonist, Viktor. There are very few direct references to the character and his history, but I could visualise who he was, and how he behaved, earning the trust of children while fulfilling orders to degrade and kill them.

Overall, I found German Fantasia to be rather depressing, as you’d expect given it’s content, but ultimately moving. Claudel’s focus on individual’s experiences provides for an impactful realisation, of how many lives were lost, changed, and altered from the second world war and the rise of fascism.

Leave a comment